Direct sum of modules

In abstract algebra, the direct sum is a construction which combines several modules into a new, larger module. The result of the direct summation of modules is the "smallest general" module which contains the given modules as submodules . This is an example of a coproduct. Contrast with the direct product, which is the dual notion.

The most familiar examples of this construction occur when considering vector spaces (modules over a field) and abelian groups (modules over the ring Z of integers). The construction may also be extended to cover Banach spaces and Hilbert spaces.

Contents |

Construction for vector spaces and abelian groups

We give the construction first in these two cases, under the assumption that we have only two objects. Then we generalise to an arbitrary family of arbitrary modules. The key elements of the general construction are more clearly identified by considering these two cases in depth.

Construction for two vector spaces

Suppose V and W are vector spaces over the field K. The cartesian product V × W can be given the structure of a vector space over K (Halmos 1974, §18) by defining the operations componentwise:

- (v1, w1) + (v2, w2) = (v1 + v2, w1 + w2)

- α (v, w) = (α v, α w)

for v, v1, v2 ∈ V, w, w1, w2 ∈ W, and α ∈ K.

The resulting vector space is called the direct sum of V and W and is usually denoted by a plus symbol inside a circle:

It is customary to write the elements of an ordered sum not as ordered pairs (v, w), but as a sum v + w.

The subspace V × {0} of V ⊕ W is isomorphic to V and is often identified with V; similarly for {0} × W and W. (See internal direct sum below.) With this identification, every element of V ⊕ W can be written in one and only one way as the sum of an element of V and an element of W. The dimension of V ⊕ W is equal to the sum of the dimensions of V and W.

This construction readily generalises to any finite number of vector spaces.

Construction for two abelian groups

For abelian groups G and H which are written additively, the direct product of G and H is also called a direct sum (Mac Lane & Birkhoff 1999, §V.6). Thus the cartesian product G × H is equipped with the structure of an abelian group by defining the operations componentwise:

- (g1, h1) + (g2, h2) = (g1 + g2, h1 + h2)

for g1, g2 in G, and h1, h2 in H.

Integral multiples are similarly defined componentwise by

- n(g, h) = (ng, nh)

for g in G, h in H, and n an integer. This parallels the extension of the scalar product of vector spaces to the direct sum above.

The resulting abelian group is called the direct sum of G and H and is usually denoted by a plus symbol inside a circle:

It is customary to write the elements of an ordered sum not as ordered pairs (g, h), but as a sum g + h.

The subgroup G × {0} of G ⊕ H is isomorphic to G and is often identified with G; similarly for {0} × H and H. (See internal direct sum below.) With this identification, it is true that every element of G ⊕ H can be written in one and only one way as the sum of an element of G and an element of H. The rank of G ⊕ H is equal to the sum of the ranks of G and H.

This construction readily generalises to any finite number of abelian groups.

Construction for an arbitrary family of modules

One should notice a clear similarity between the definitions of the direct sum of two vector spaces and of two abelian groups. In fact, each is a special case of the construction of the direct sum of two modules. Additionally, by modifying the definition one can accommodate the direct sum of an infinite family of modules. The precise definition is as follows (Bourbaki 1989, §II.1.6).

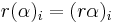

Let R be a ring, and {Mi : i ∈ I} a family of left R-modules indexed by the set I. The direct sum of {Mi} is then defined to be the set of all sequences  where

where  and

and  for cofinitely many indices i. (The direct product is analogous but the indices do not need to cofinitely vanish.)

for cofinitely many indices i. (The direct product is analogous but the indices do not need to cofinitely vanish.)

It can also be defined as functions α from I to the disjoint union of the modules Mi such that α(i) ∈ Mi for all i ∈ I and α(i) = 0 for cofinitely many indices i. These functions can equivalently be regarded as finitely supported sections of the fiber bundle over the index set I, with the fiber over  being

being  .

.

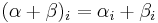

This set inherits the module structure via component-wise addition and scalar multiplication. Explicitly, two such sequences (or functions) α and β can be added by writing  for all i (note that this is again zero for all but finitely many indices), and such a function can be multiplied with an element r from R by defining

for all i (note that this is again zero for all but finitely many indices), and such a function can be multiplied with an element r from R by defining  for all i. In this way, the direct sum becomes a left R-module, and it is denoted

for all i. In this way, the direct sum becomes a left R-module, and it is denoted

It is customary to write the sequence  as a sum

as a sum  . Sometimes a primed summation

. Sometimes a primed summation  is used to indicate that cofinitely many of the terms are zero.

is used to indicate that cofinitely many of the terms are zero.

Properties

- The direct sum is a submodule of the direct product of the modules Mi (Bourbaki 1989, §II.1.7). The direct product is the set of all functions α from I to the disjoint union of the modules Mi with α(i)∈Mi, but not necessarily vanishing for all but finitely many i. If the index set I is finite, then the direct sum and the direct product are equal.

- Each of the modules Mi may be identified with the submodule of the direct sum consisting of those functions which vanish on all indices different from i. With these identifications, every element x of the direct sum can be written in one and only one way as a sum of finitely many elements from the modules Mi.

- If the Mi are actually vector spaces, then the dimension of the direct sum is equal to the sum of the dimensions of the Mi. The same is true for the rank of abelian groups and the length of modules.

- Every vector space over the field K is isomorphic to a direct sum of sufficiently many copies of K, so in a sense only these direct sums have to be considered. This is not true for modules over arbitrary rings.

- The tensor product distributes over direct sums in the following sense: if N is some right R-module, then the direct sum of the tensor products of N with Mi (which are abelian groups) is naturally isomorphic to the tensor product of N with the direct sum of the Mi.

- Direct sums are also commutative and associative (up to isomorphism), meaning that it doesn't matter in which order one forms the direct sum.

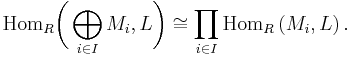

- The group of R-linear homomorphisms from the direct sum to some left R-module L is naturally isomorphic to the direct product of the groups of R-linear homomorphisms from Mi to L:

-

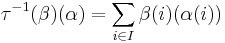

- Indeed, there is clearly a homomorphism τ from the left hand side to the right hand side, where τ(θ)(i) is the R-linear homomorphism sending x∈Mi to θ(x) (using the natural inclusion of Mi into the direct sum). The inverse of the homomorphism τ is defined by

- for any α in the direct sum of the modules Mi. The key point is that the definition of τ−1 makes sense because α(i) is zero for all but finitely many i, and so the sum is finite.

- In particular, the dual vector space of a direct sum of vector spaces is isomorphic to the direct product of the duals of those spaces.

-

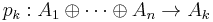

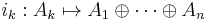

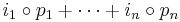

- The finite direct sum of modules is a biproduct: If

-

- are the canonical projection mappings and

- are the inclusion mappings, then

- equals the identity morphism of A1 ⊕ ··· ⊕ An, and

- is the identity morphism of Ak in the case l=k, and is the zero map otherwise.

-

Internal direct sum

Suppose M is some R-module, and Mi is a submodule of M for every i in I. If every x in M can be written in one and only one way as a sum of finitely many elements of the Mi, then we say that M is the internal direct sum of the submodules Mi (Halmos 1974, §18). In this case, M is naturally isomorphic to the (external) direct sum of the Mi as defined above (Adamson 1972, p.61).

A submodule N of M is a direct summand of M if there exists some other submodule N′ of M such that M is the internal direct sum of N and N′. In this case, N and N′ are complementary subspaces.

Universal property

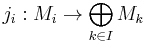

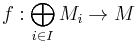

In the language of category theory, the direct sum is a coproduct and hence a colimit in the category of left R-modules, which means that it is characterized by the following universal property. For every i in I, consider the natural embedding

which sends the elements of Mi to those functions which are zero for all arguments but i. If fi : Mi → M are arbitrary R-linear maps for every i, then there exists precisely one R-linear map

such that f o ji = fi for all i.

Dually, the direct product is the product.

Grothendieck group

The direct sum gives a collection of objects the structure of a commutative monoid, in that the addition of objects is defined, but not subtraction. In fact, subtraction can be defined, and every commutative monoid can be extended to an abelian group. This extension is known as the Grothendieck group. The extension is done by defining equivalence classes of pairs of objects, which allows certain pairs to be treated as inverses. The construction, detailed in the article on the Grothendieck group, is "universal", in that it has the universal property of being unique, and homomorphic to any other embedding of an abelian monoid in an abelian group.

Direct sum of modules with additional structure

If the modules we are considering carry some additional structure (e.g. a norm or an inner product), then the direct sum of the modules can often be made to carry this additional structure, as well. In this case, we obtain the coproduct in the appropriate category of all objects carrying the additional structure. Three prominent examples occur for algebras over a field, Banach spaces and Hilbert spaces.

Direct sum of algebras

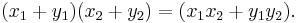

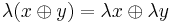

A direct sum of algebras X and Y is the direct sum as vector spaces, with product

Consider these classical examples:

has been studied as split-complex numbers,

has been studied as split-complex numbers, is the algebra of tessarines introduced by James Cockle in 1848, and

is the algebra of tessarines introduced by James Cockle in 1848, and , called the split-biquaternions, was introduced by William Kingdon Clifford in 1873.

, called the split-biquaternions, was introduced by William Kingdon Clifford in 1873.

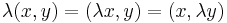

Joseph Wedderburn exploited the concept of a direct sum of algebras in his classification of hypercomplex numbers. See his Lectures on Matrices (1934), page 151. Wedderburn makes clear the distinction between a direct sum and a direct product of algebras: For the direct sum the field of scalars acts jointly on both parts:  while for the direct product a scalar factor may be collected alternately with the parts, but not both:

while for the direct product a scalar factor may be collected alternately with the parts, but not both: .

.

Ian R. Porteous uses the three direct sums above, denoting them  , as rings of scalars in his analysis of Clifford Algebras and the Classical Groups (1995).

, as rings of scalars in his analysis of Clifford Algebras and the Classical Groups (1995).

Direct sum of Banach spaces

The direct sum of two Banach spaces X and Y is the direct sum of X and Y considered as vector spaces, with the norm ||(x,y)|| = ||x||X + ||y||Y for all x in X and y in Y.

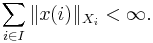

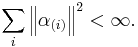

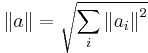

Generally, if Xi is a collection of Banach spaces, where i traverses the index set I, then the direct sum ⊕i∈I Xi is a module consisting of all functions x defined over I such that x(i) ∈ Xi for all i ∈ I and

The norm is given by the sum above. The direct sum with this norm is again a Banach space.

For example, if we take the index set I = N and Xi = R, then the direct sum ⊕i∈N is the space l1, which consists of all the sequences (ai) of reals with finite norm ||a|| = ∑i |ai|.

A closed subspace A of a Banach space X is complemented if there is another closed subspace B of X such that X is equal to the internal direct sum  . Note that not every closed subspace is complimented, eg. c0 is not complimented in

. Note that not every closed subspace is complimented, eg. c0 is not complimented in  .

.

Direct sum of Hilbert spaces

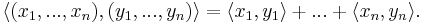

If finitely many Hilbert spaces H1,...,Hn are given, one can construct their direct sum as above (since they are vector spaces), and then turn the direct sum into a Hilbert space by defining the inner product as:

This turns the direct sum into a Hilbert space which contains the given Hilbert spaces as mutually orthogonal subspaces.

If infinitely many Hilbert spaces Hi for i in I are given, we can carry out the same construction; notice that when defining the inner product, only finitely many summands will be non-zero. However, the result will only be an inner product space and it won't be complete. We then define the direct sum of the Hilbert spaces Hi to be the completion of this inner product space.

Alternatively and equivalently, one can define the direct sum of the Hilbert spaces Hi as the space of all functions α with domain I, such that α(i) is an element of Hi for every i in I and:

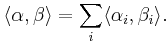

The inner product of two such function α and β is then defined as:

This space is complete and we get a Hilbert space.

For example, if we take the index set I = N and Xi = R, then the direct sum ⊕i∈N Xi is the space l2, which consists of all the sequences (ai) of reals with finite norm  . Comparing this with the example for Banach spaces, we see that the Banach space direct sum and the Hilbert space direct sum are not necessarily the same. But if there are only finitely many summands, then the Banach space direct sum is isomorphic to the Hilbert space direct sum, although the norm will be different.

. Comparing this with the example for Banach spaces, we see that the Banach space direct sum and the Hilbert space direct sum are not necessarily the same. But if there are only finitely many summands, then the Banach space direct sum is isomorphic to the Hilbert space direct sum, although the norm will be different.

Every Hilbert space is isomorphic to a direct sum of sufficiently many copies of the base field (either R or C). This is equivalent to the assertion that every Hilbert space has an orthonormal basis. More generally, every closed subspace of a Hilbert space is complemented: it admits an orthogonal complement. Conversely, the Lindenstrauss–Tzafriri theorem asserts that if every closed subspace of a Banach space is complemented, then the Banach space is isomorphic (topologically) to a Hilbert space.

See also

References

- Iain T. Adamson (1972), Elementary rings and modules, University Mathematical Texts, Oliver and Boyd, ISBN 0-05-002192-3

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1989), Elements of mathematics, Algebra I, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-64243-9.

- Dummit, David S.; Foote, Richard M. (1991), Abstract algebra, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc., ISBN 0-13-004771-6.

- Halmos, Paul (1974), Finite dimensional vector spaces, Springer, ISBN 0387900934

- Mac Lane, S.; Birkhoff, G. (1999), Algebra, AMS Chelsea, ISBN 0-8218-1646-2.